Basic Theories for Tutoring

Like any field, Writing Centers have pedagogies, or a set of teaching theories we often use as a basis for our work. These are just theories, ways of explaining what we do; you need not subscribe to any one particular theory, and you need not agree with all (or any!) of them. Writing Center pedagogies can also be quite binary; that is, they tend to frame ideas in as either/or rather than a spectrum. As you read, think about how these binary ideas can be productive, but also how they can limit ways of thinking.

All of these have their pros and cons, and you’ll sometimes find that some Writing Center and Composition theorists tend to point out more problems than solutions. This section is simply meant to give you some background for thinking about how Writing Centers operate.

HOCs vs. LOCs

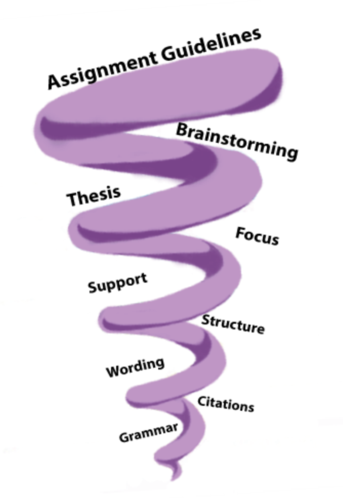

One traditional idea in Writing Center pedagogy is “HOCs before LOCs.” These acronyms stand for “Higher Order Concerns” and “Lower Order Concerns.” The difference is simple: HOCs are global issues, or issues that affect how a reader understands the entire paper; LOCs are issues that don’t necessarily interrupt understanding of the writing by themselves. Some examples of HOCs are thesis, development of ideas, focus, or audience. Some LOCs are grammar, punctuation, and spelling. Different Writing Centers have different ways of framing this idea. Highline’s WC uses the “spiral of priorities” to illustrate it.

Spiral of priorities. From top to bottom: assignment guidelines, brainstorming, thesis, focus, support, structure, wording, citations, grammar.

Are HOCs more important than LOCs?

No, not necessarily. HOCs tend to interrupt a reader’s understanding of the writing, and that’s why they need to be addressed first. However, if a LOC becomes a major obstacle, then it naturally becomes a higher priority. For example, if you’re not sure what a writer’s thesis statement is saying because the sentence structure makes it hard to understand, or if verb tense errors make the paper as a whole really difficult to read, it would be challenging, if not impossible, for the reader to grasp the paper’s ideas.

In short, it’s important to figure out and address the things that affect your ability to understand and follow the paper easily.

Something to think about

A writer comes to you and says, “I’d like you to check my grammar.” Keeping in mind the “HOCs before LOCs” guidelines, and also remembering that the Writing Center is writer-centered, what should you do?

Process vs. Product

Over the years in the field of Composition, there has been a paradigm shift. Do you remember the way you were taught how to write a paper in middle school? High school? Did you receive any guidance while you wrote, or did you just receive the assignment sheet and a set of guidelines? Were you allowed to revise after you turned your paper in, or did you just receive a grade? Were there any comments from the teacher on your writing? (For me, as someone in my 30s, not really!)

For a long time, professionals assumed that you couldn’t teach writing. They assumed that it was a skill writers would learn simply by example, or by being forced to practice writing. Writers received little guidance while they wrote because teachers were primarily concerned with the product. To that end, the writing classroom became a place where writers were taught grammar rules and vocabulary. They practiced writing, and then they were given a grade. However, teachers discovered that the product wasn’t getting any better. They began to discover what they really knew all along: that writing isn’t just a skill, but a process that occurs in several stages. If they could intervene in that process, they could improve the product.

Writing Centers subscribe to this process-over-product model. Though writers bring us a product (their papers or projects), it is our job to do some detective work and investigate the writer’s process so we can help them improve it. It is important to address the paper in front of you in the moment, but it’s also important to address the larger process behind the product. Think in terms of developing skills while making “fixes.” Make it your goal during each session to teach the writer one thing that will help them improve their writing process. How can they apply skills from one paper to the next?

Paradigms of Composition

A paradigm is a way of thinking about something, or a model of it. In the field of Composition, three models are most often identified: cognitivism, expressivism, and social constructivism. These describe what writing is, how it’s done, and why we do it.

Some theorists believe that these paradigms appeared in a certain order: cognitivism came first, followed by expressivism, and social constructivism is sometimes thought to be the most recent development. These distinctions are by no means exclusive or exhaustive, and the lines between each paradigm frequently blur. Think of these as ways of looking at the way people write.

(Keep in mind that this is a very brief overview of these paradigms, and meant to give you a reference and a basic understanding of where these schools of thought come from.)

| Cognitivism | Expressivism | Social Constructivism | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Writing is... | A function of cognitive process (goal is efficiency and clarity) | A way to express what is inside us (deep and personal) | A way to construct meaning |

| We write to.... | Learn | Discover meaning | Construct meaning |

| The writer is... | Problem solver, goal-setter | Thinker, discoverer | Meaning-maker |

| The text/essay... | Plays a minimal role—the thinking behind the text is more important | Is personal rather than social; expressing thought is more important than correctness | Is in conversation with other texts; doesn't mean much on its own |

| The writing process... | Happens in three stages: planning, writing, revising | Involves freewriting, “discovery” drafts | Happens socially rather than individually |

| Can we teach writing? | Yes—we can teach students how to become problem-solvers and goal-setters | No—but we can facilitate an environment of discovery | We can't teach a "correct" way to write, but we can teach conventions within the context of a community |

| Who is a writer? | A person who sets goals | The lens through which the creative force flows | A member of a discourse community |

| Paradigm's contribution to our work | Basics of the writing process; problem-solving approach to writing | Peer reviews, class discussions | The idea of writing as political in nature; discourse communities; conventions vs. rules |

Minimalist vs. Directive Tutoring

The debate between minimalist vs. directive (or directive vs. non-directive) tutoring is often closely linked with the discussion of process vs. product and HOCs vs. LOCs.

In a session, who should talk more, the tutor or the writer? Who should hold the pen? What kind of issues should the session address first? Should tutors provide answers for writers?

There are, of course, advantages and disadvantages to both of these methods. Critics and supporters of both of them often make assumptions about this debate.

Assumptions about higher order concerns

Addressing higher order concerns involves

- Helping a writer compose

- Helping a writer think

- Helping a writer understand content

Assumptions about lower order concerns

Addressing lower order concerns involves

- Helping the writer learn specific skills

- Breaks writing down into skills rather than thought and communication

Assumptions about minimalist tutoring

In minimalist tutoring…

- the writer should be “active” and do most of the talking

- the tutor should be an indirect leader

- the tutor should use leading questions (Socratic Method)

- is descriptive rather than prescriptive

- the tutor should never write on a writers’ paper

- individualism is valued

- the goal is to wean the writer off needing the Writing Center

Assumptions about directive tutoring

In directive tutoring…

- the tutor does the talking, creating a “passive” writer

- the tutor directs the writer where the tutor thinks they need to go

- the tutor gives directions (is prescriptive)

- the tutor can hold the pen and write on the writer’s paper

- relationships are valued

- sessions create dependence between writer and tutor

Minimalist Perspective: Jeff Brooks

In his article called “Minimalist Tutoring: Making the Student Do All the Work,” Jeff Brooks argues,

The student, not the tutor, should ‘own’ the paper and take full responsibility for it’. The tutor should take on a secondary role, serving mainly to keep the student focused on his own writing. A student who comes to the writing center and passively receives knowledge from a tutor will not be any closer to his or her own paper than he was when he walked in. He may leave with an improved paper, but he will not have learned much.

A writing teacher or tutor cannot and should not expect to make student papers ‘better’; that is neither our obligation, nor is it a realistic goal. The moment we consider it our duty to improve the paper, we automatically relegate ourselves to the role of editor. (220)

Brooks advises tutors to be careful to avoid appropriation, or taking over a writer’s paper. To avoid this, he writes, tutors should take steps to make sure the writer is in charge:

- Sit beside the writer, not across the desk.

- Try to get the writer to be physically closer to the paper than you are.

- Never write on the paper. If you are right handed, sit on the writer’s right. This will reduce the temptation by making it more difficult.

- Have the writer read the paper aloud to you, and suggest that he hold a pencil while doing so.

- Get the writer to talk. (Brooks 221-223)

If a writer is resistant to these methods, Brooks suggests the following:

When a student acts disinterested, leaning back from the paper or even turning away, borrow student body language and do the same. This language will speak clearly to the student: “You cannot make me edit your paper.”

Be completely honest with a student who is giving you a hard time. If she says, “What should I do here?” you can say in a friendly, non-threatening way, “I can’t tell you that—it’s your grade, not mine,” or, “I don’t know—it’s your paper.” (Brooks 223)

It’s easy to see the benefits of nondirective/minimalist tutoring. Using these methods, there is little chance of appropriation, and the writer is responsible for his/her own writing. But what issues could arise?

A Critique of the Minimalist Perspective: Shamoon and Burns

Linda Shamoon and Deborah Burns take issue with nondirective methods in their article, “A Critique of Peer Tutoring.” They question the efficiency of nondirective methods and recount experiences they and other successful writers have had with very directive methods of tutoring and instruction:

[Deborah Burns’] director was directive, he substituted his own words for hers, and he stated with disciplinary appropriateness the ideas with which she had been working. Furthermore, Burns observed that other graduate students had the same experience as this director: he took their papers and rewrote them while they watched. (229)

If you find yourself startled by these methods, Burns was, too! However, Burns goes on to write,

[Students] left feeling better able to complete their papers, and they tackled other papers with greater ease and success….For Burns and for others, when the director intervened, a number of thematic, stylistic, and rhetorical issues came together in a way that revealed and made accessible aspects of the discipline which had remained unexplained or out of reach. Instead of appropriation, this event may knowledge and achievement accessible.

Shamoon and Burns explore “alternative tutorial practices,” describing master classes in music, in which the instructor is frequently directive, making suggestions and corrections as to writers’ technique while other writers watch. They describe a sense of accomplishment and community watching one writer at a time be instructed (directed) by a mentor. The mentor used all of the techniques described in the “Directive Tutoring” list above.

Muriel Harris describes another alternative technique she uses with novice writers in her article “Modeling: A Process Method of Teaching.” She modeled her own writing process with a writer named Mike and then asked him to copy her techniques and behaviors. She writes, “What better way is there to convince writers that writing is a process that requires effort, thought, time and persistence than to go through all that writing, scratching out, rewriting and revising with and for our writers?” (Harris, qtd. in Shamoon and Burns 235).

The focus of these alternative practices is imitation as learning. Shamoon and Burns argue that writers often learn as much (if not more) by watching and imitating the behavior of an experienced practitioner than by merely being prompted and encouraged. “Not only does directive tutoring support imitation as a legitimate practice,” they write, “it allows both writer and tutor to be the subjects of the tutoring session (while nondirective tutoring allows only the writer’s work to be the center of the tutoring session)” (236). They imply that this method is closer to the true spirit of collaboration and conversation that we strive for in Writing Centers.

Consider these very different methods, as well as the following questions.

- What are the benefits and drawbacks of each method?

- Do these methods keep in mind both the tutor’s and the writer’s agenda during the session?

- Imagine if you were a writer and you were the subject of these methods. How would you react?

- What practices appeal to you about directive methods? About non-directive methods?

- Are there certain tutoring situations in which you could see yourself using one method or the other?

- Do you think non-directive methods might be better for an experienced writer or a novice writer? What about directive methods?